🦠 IMMUNE RESPONSE TO FUNGAL INFECTIONS

- ToothOps

- Jan 15

- 4 min read

A ToothOps Guide for Dental Students, Pre-Dentals & Curious Minds

Fungal infections are one of the most fascinating — and misunderstood — topics in immunology. Unlike bacteria and viruses, fungi are eukaryotes with unique cell walls and slow replication cycles. Most of the time, our bodies win easily. But when immunity drops, fungi take the opportunity to invade.

This guide breaks down exactly how the immune system fights fungi, with a special focus on the oral cavity, granulomas, and the innate vs. adaptive responses — in a way that’s exam-friendly, clinically relevant, and easy to remember.

Let’s dive in.

⭐ 1. Why Humans Are Naturally Resistant to Fungi

Most people with normal immunity rarely develop serious fungal infections because:

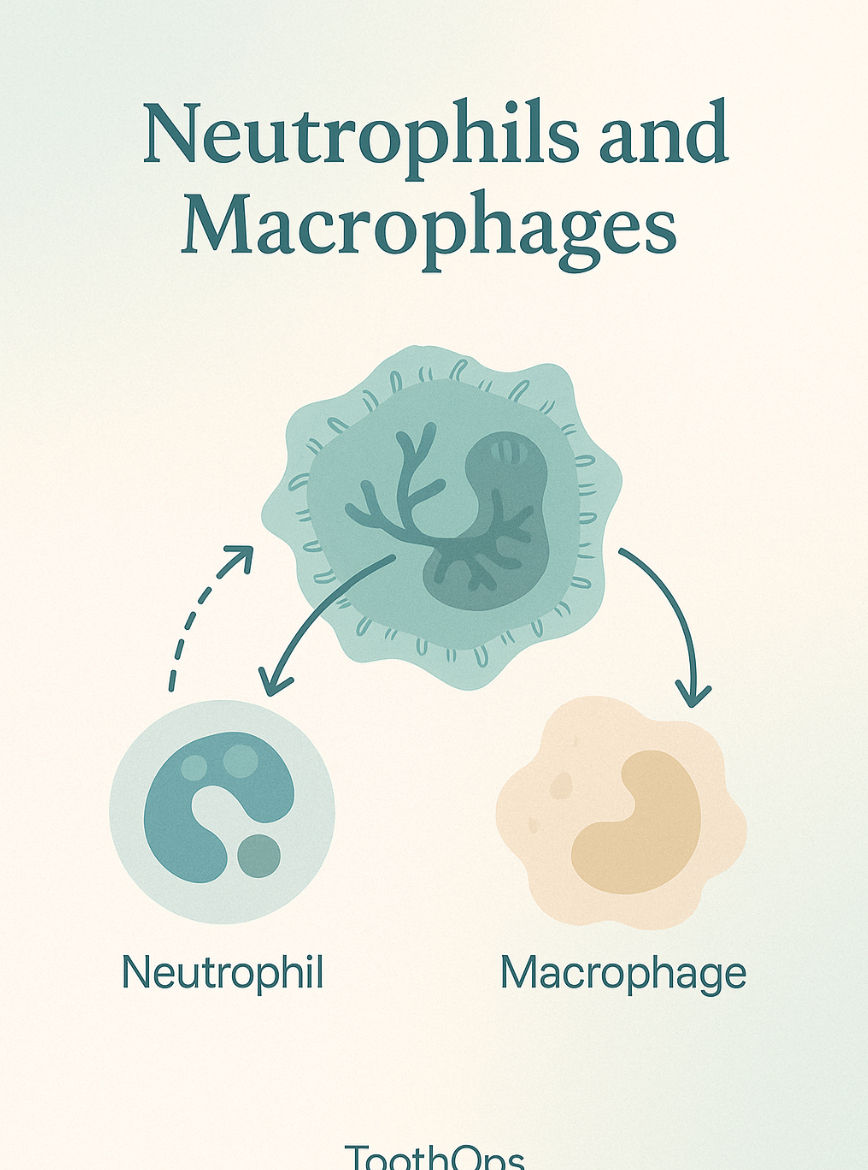

Neutrophils and macrophages rapidly kill most fungal spores

Our intact skin and mucosa act as strong physical barriers

Saliva contains antifungal proteins (histatins, lysozyme, lactoferrin)

The immune system can form granulomas when fungi survive inside macrophages

Still, in the right conditions — immunosuppression, xerostomia, antibiotic use, diabetes — fungi can shift from harmless colonizers to invasive pathogens.

⭐ 2. Candida albicans — The Opportunist Among Us

Candida albicans lives in the oral cavity, GI tract, and vagina as part of the normal flora.

In healthy hosts, it stays controlled.

In immunocompromised or dry-mouth environments, it overgrows and switches from yeast → hyphal form — increasing invasion and virulence.

What triggers overgrowth?

Xerostomia

Diabetes

Dentures (especially uncleaned)

Broad-spectrum antibiotics

Inhaled corticosteroids

High carbohydrate diets

Clinical forms in dentistry:

Pseudomembranous candidiasis (“thrush”)

Erythematous candidiasis

Denture stomatitis

Angular cheilitis

⭐ 3. Granulomas in Fungal Infections

Many systemic fungal infections produce granulomas, including:

Histoplasmosis

Coccidioidomycosis

Blastomycosis

Cryptococcosis

Granulomas form when fungi cannot be fully eliminated, prompting the immune system to wall them off.

Key pathway:

Dendritic cells + macrophages present antigen

CD4+ T-cells → differentiate into Th1 cells

Th1 cells release IFN-γ

Macrophages activate, transform into epithelioid cells

Some fuse into multinucleated giant cells

Fibroblasts lay collagen → forming a structured granuloma

🧠 Clinical pearl: Caseating granulomas often suggest TB or fungal infections, while non-caseating granulomas (no necrosis) are common in sarcoidosis.

⭐ 4. First Line of Defense: Skin, Mucosa & Saliva

Skin & epithelial barriers

Healthy skin stops dermatophytes and opportunistic fungi.

Damaged or macerated skin → fungal invasion becomes possible.

Respiratory & mucosal defenses

Nasopharyngeal mucosa traps and filters spores.

Alveolar macrophages engulf most inhaled fungi before infection occurs.

Humoral immunity:

Systemic fungal infections trigger production of IgG and IgM, aiding opsonization.

But antibodies alone rarely clear fungi — cell-mediated immunity is the true hero.

⭐ 5. Fungal Immune Evasion Strategies

Pathogenic fungi have evolved ways to survive our immune system, such as:

Antioxidant enzymes to neutralize ROS

Cell wall masking (hiding β-glucans from PRRs like Dectin-1)

Thick capsules (Cryptococcus) to prevent phagocytosis

Dimorphic switching (yeast ↔ mold)

Biofilm formation — critical for Candida on dentures, implants, and mucosa

These survival strategies explain why fungal infections are often chronic and sometimes recurrent.

⭐ 6. Immune Response Process (Innate → Adaptive)

Innate response: Rapid, nonspecific

Neutrophils are the primary killers of fungi

Use oxidative burst, NETs, and antimicrobial peptides

Macrophages engulf spores, release cytokines, and activate T-cells

Dendritic cells capture fungal antigens and migrate to lymph nodes

NK cells release perforin and granzyme against infected host cells

Key cytokines + signals:

IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α → inflammation

IL-12 → drives Th1 differentiation

IL-17 → crucial for mucosal candidiasis defense (Th17 pathway)

⭐ 7. Adaptive Immunity Against Fungi

Th1 Response (Most important for systemic fungi)

IFN-γ activates macrophages

Critical for Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides

Th17 Response (Critical for oral & mucosal fungi)

IL-17 & IL-22 recruit neutrophils and stimulate epithelial antimicrobial peptides

Plays a central role in preventing oral candidiasis

Antibodies:

IgG and IgM aid opsonization, but fungi are often resistant to antibody-mediated killing.

IgA dominates the oral cavity, preventing adherence and biofilm formation.

⭐ 8. Antifungal Drugs — How They Work

Antifungal medications target structures unique to fungal cells, such as:

Ergosterol (instead of cholesterol)

Polyenes bind it (amphotericin B)

Azoles inhibit its synthesis

Allylamines (terbinafine) block squalene epoxidase

β-glucan in fungal cell walls

Echinocandins inhibit β-glucan synthase

These unique pathways allow us to treat fungi without harming human cells (at least in theory — amphotericin B nephrotoxicity still says hello).

⭐ 9. Oral Fungal Infections: Innate Defense

(High yield for dentistry)

Oral innate defenses include:

Salivary flow

Antimicrobial peptides such as histatins, which specifically damage Candida

Neutrophils patrolling the gingival crevice

Normal oral microbiota competing with fungal colonizers

Mechanical cleansing from mastication and swallowing

Macrophages survive longer than neutrophils, helping maintain chronic surveillance in mucosa.

⭐ 10. Oral Fungal Infections: Adaptive Defense

Adaptive responses include humoral (IgA) and cell-mediated immunity.

In the oral cavity, the most important immunoglobulin is secretory IgA (sIgA), which:

Agglutinates Candida

Blocks adhesion to epithelial surfaces

Helps maintain healthy microbial balance

Th17 responses are especially important — patients with IL-17 deficiencies often develop chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

⭐ 11. ToothOps Clinical Takeaways for Dentistry

You will see fungal infections often. Look for:

Red or white patches that scrape off

Glossy red tongue (erythematous candidiasis)

Denture-associated erythema

Angular cheilitis

Burning sensation with no visible lesions (early infection)

Patients at increased risk:

Diabetics

Xerostomia patients (radiation, medications, Sjögren’s)

Denture wearers

Immunocompromised individuals

Asthma/COPD patients using steroid inhalers

What you can do as a dental provider:

Encourage denture hygiene + overnight removal

Recommend rinsing after steroid inhaler use

Evaluate for systemic contributors (diabetes, hyposalivation, meds)

Prescribe antifungals appropriately (nystatin, clotrimazole, fluconazole)

Educate patients on prevention and recurrence management

Comments